-

Description

-

The Venus de’ Medici depicts the goddess according to the iconographic type known as the Venus Pudica, in which the figure instinctively covers her breasts and pubis, as if she had become aware of an indiscreet gaze. This model derives from the Aphrodite of Knidos by Praxiteles (4th century BC) and enjoyed wide diffusion during the Hellenistic and Roman periods. An inscription on the base attributes the statue to Cleomenes, son of Apollodorus, an Athenian sculptor.

The statue was discovered in Rome in the first half of the sixteenth century, in the area of the Baths of Trajan, in a fragmented but exceptionally well-preserved condition. Since it lacked an artist’s signature, the base of another ancient statue—signed by Cleomenes but too poorly preserved to be restored—was adapted to it. This operation permanently associated the sculpture with Cleomenes’ name, albeit incorrectly.

Acquired by Ferdinando de’ Medici, the Venus was kept for a long time at Villa Medici in Rome before being transferred to Florence in 1677. There it underwent only minimal restoration, limited mainly to the reintegration of a few missing fingers. In 1680 it was placed in the Tribuna of the Uffizi, where it became one of the most admired sculptures of the Grand Tour, largely escaping further restoration. An attempt to replace the arms in 1785 was rejected.

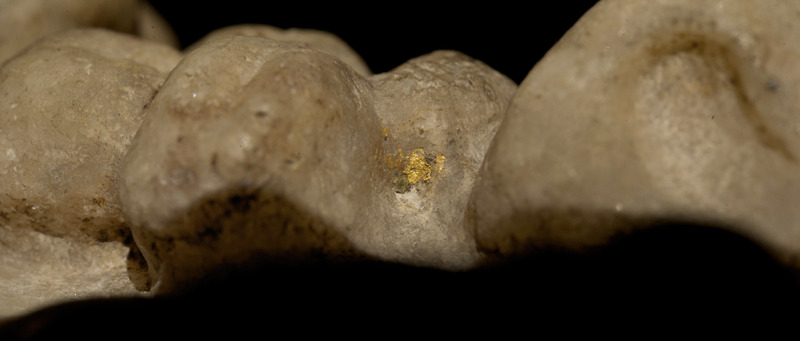

In 1802 the statue was requisitioned by the French and taken to Paris, where it remained until 1816, when it was returned to Florence following the Treaty of Vienna. Eighteenth-century sources recall that the Venus’s hair was originally gilded, but this feature appears to have disappeared in the nineteenth century, possibly due to a deliberate removal of the gilding during the Neoclassical period.

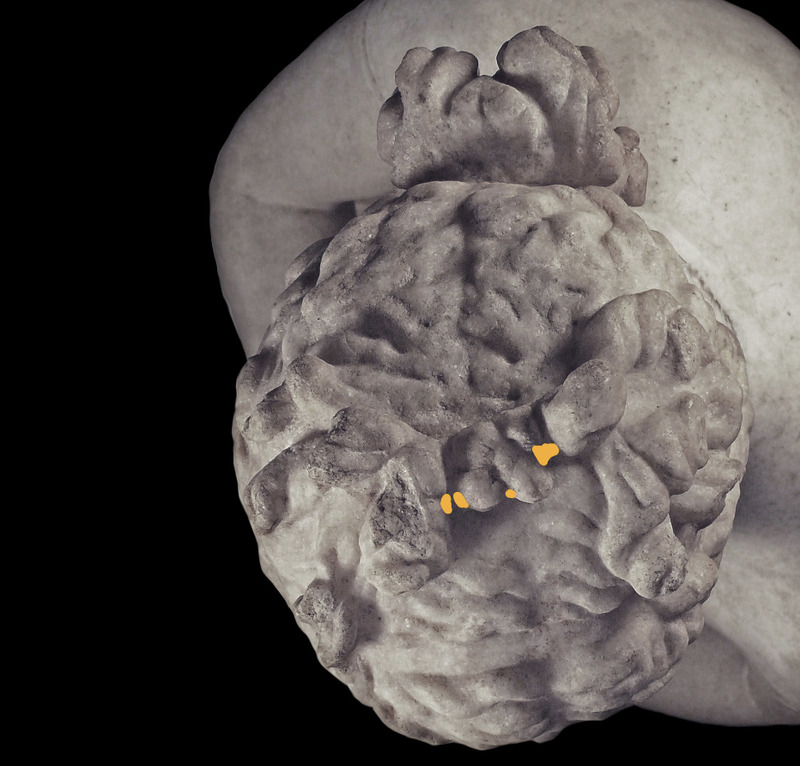

The restorations carried out in 2012 confirmed that the statue was originally polychrome: traces of gilding, cinnabar on the lips, and Egyptian blue on the dolphin attest to this, as do the pierced earlobes, which were intended to hold metal jewelry.

Since the signature of Cleomenes did not originally belong to this sculpture, attempts to date it on the basis of the genealogy of the Cleomenes family are unfounded. Nevertheless, stylistic comparisons with other works allow the Venus to be dated between the late second and early first century BC. Cleomenes, son of Apollodorus, was therefore a real artist, but not the author of the statue—a name that, due to an ancient error, became permanently associated with a masterpiece he never created.