Officer as Mars (inv. no. C932)

Item

- Other Media

-

C932_fig. 1

C932_fig. 1 -

C932_fig. 2

C932_fig. 2 - Description

-

This slightly over life-size male statue (h. 141 cm) is based on the Diomedes model attributed to the sculptor Kresilas, with several variations in the turn of the head, the gesture of the left arm, and the position of the cloak and baldric. It has been dated to the late Hadrianic period and attributed to the emperor himself by P. Gauckler, H. P. L’Orange, and H. G. Niemeyer, on account of the physiognomic similarity to the emperor and the use of the Diomedes model, as in the examples from Vaison, Pergamon, and Perge.

However, the Carthage statue deviates from the Diomedes type in that it is helmeted, a feature that tends to associate it more closely with Mars. Moreover, while helmeted portraits of Hadrian are rare, standing helmeted statues are even rarer, and—with the exception of the example in the Bardo—they generally follow the Mars Borghese type, whether representing emperors, such as the Hadrian in the Capitoline Museums, or unidentified figures. The identification with Hadrian had already been rejected by M. Wegner and was later largely abandoned by C. Evers, who did not recognise in it any of the documented official portrait types of this emperor.

More recently, it has dismissed the attribution to Hadrian altogether, interpreting the statue instead as a fine example of Angleichung relative to the emperor’s portraits, representing an unknown but prominent citizen who chose to emphasize his military and heroic character - Typology

- Portrait

- Definition

- Officer as Mars (inv. no. C932)

- Collection

- Tunis, Bardo National Museum.

- Inventory number

- C932

- Provenance

- Carthage, cisterns of the Odeon

- Date

- 2nd century C.E.

- Material

- White marble

- Dimensions

- H 141 cm

- Analytical methods

- VIS

- VIL

- UV

- MO VIS

- MO UV

- Autoptic examination

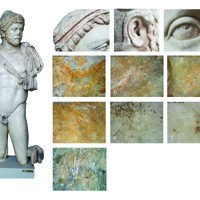

- Visual examination of the statue revealed the presence of previously undocumented paint traces, which had not been mentioned either in the bibliography or during the excavations of the Odeon. Traces in various shades of yellow, visible to the naked eye, survive over large areas: the flesh (right ear, lacrimal caruncles, eyelids, labial groove, neck, left shoulder, navel, pubic area), the hair and beard, as well as the military attributes (helmet — left side and back —, baldric, the folded pallium, and the fibula).

- Imaging

-

Microscopic examination across 300 observation points made it possible to clarify the nature and application of these traces. A very thin, almost translucent pale yellow layer is present on the flesh; a darker and thicker tone is observed in shadowed areas such as the hollow of the ear, between the lips, and in the navel. The outline of the eyes is also marked by small black dots, probably the result of a degraded line.

The helmet bears a thicker orange-yellow layer than the pallium. The drapery on the shoulder is darker, with a rust-coloured tone, and the fibula is black-brown along the edges and pale yellow at the centre. The beard and hair alternate between warm yellow and bronze-yellow locks. In the recesses of the beard on the left side, remains of gold leaf are preserved—undetectable to the naked eye. - Under painting traces

- Black lines around the eyes

- Pigments

- Yellow, orange, brown, gold leaf.

- Binder

- n.d.

- Stratigraphy

- Directly on the marble

- Shading

- Darker shading in the recesses

- Metallic traces

- On the beard

- Tools marks

-

Scraping traces on the edge of the drapery

- Apparent marble parts

- no

- Restorations

- no

- Polychromy technique

- The back of the statue shows the same refined treatment as the front, indicating that it must have been placed on a base also intended to be viewed from behind.

- Imitation of other supports

- metal

- Polychromy type

-

The high quality of the statue’s execution is further underscored by the very fine and translucent polychrome treatment, achieved by applying highly diluted paint. The fact that the gold leaf is preserved only on the beard—an important area, admittedly—does not allow us to determine whether the gilding originally covered the entire statue or only selected parts. The edge of the pallium, however, must have been gilded, as clear traces of the removal of the gold leaf are visible along its lower border. Assuming partial gilding (fig. 5), the statue may be interpreted in two ways. In the first scenario, the gold leaf may have been applied sparingly to the beard in order to create effects of light, as has been proposed for the hair of the portrait of a young Roman (inv. 821) in the Glyptotek in Copenhagen. This aesthetic treatment may be linked to the cosmetic practice of sprinkling the hair and beard with gold dust to enhance their lustre.

In the second scenario, the beard and the edge of the pallium may have been entirely gilded, creating a contrast with the other painted areas. If partial gilding is assumed, it cannot be excluded that other parts or attributes were also highlighted with gold—for instance the hair, the pubic area, the helmet, or the baldric—while the flesh would have received a different treatment. This type of polychrome scheme, observed in stone Greek statues imitating chryselephantine works, appears to be the most common in the Roman period, as it allows the symbolic attributes of the deity or of the portrait to be emphasised through the use of gold. It is also possible that the painted layers on the statue served as a preparatory ground for gilding, and that the surviving traces represent only a small remnant of gold leaf that may once have covered the entire statue.