Bust of the god Serapis (inv. no. B 158)

Item

- Other Media

-

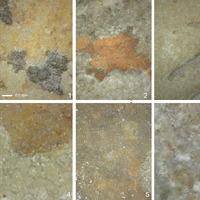

B 158.fig.1

B 158.fig.1 -

B 158. fig.2

B 158. fig.2 -

B 158. fig.4

B 158. fig.4 -

B 158. fig.5

B 158. fig.5 -

B 158. fig.6

B 158. fig.6 - Description

-

Serapis, without the modius, is depicted with thick hair arranged in locks that fall as bangs on the forehead, a beard twisted into volutes and parted in the center. The god wears a chiton.

The Mariemont bust belongs to the “fringe” type (Fransentypus). The use of a drill, the marble’s surface finish and the similarities with the Severan head in the Albani villa collection support assigning the Mariemont bust to the early Severan period, i.e., late 2nd century AD.

The studies suggest its origin from Rome, specifically from dredging operations on the Tiber, before being acquired by French banker Léopold Goldschmidt in 1891. However, its exact find-spot remains unknown. - Definition

- Bust of the god Serapis (inv. no. B 158)

- Collection

- Mariemont, Musées Royaux

- Inventory number

- B 158

- Date

- Late 2nd century CE

- Material

- White marble

- Dimensions

- Height: 58 cm

- Analytical methods

- VIS

- UV

- MAXRF

- Autoptic examination

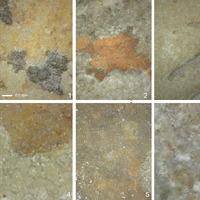

- The marble displays visible traces of color on the hair, beard, face, and drapery.

-

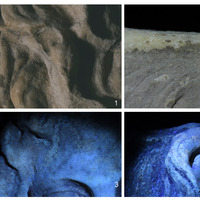

B 158. fig.3

B 158. fig.3

- Imaging

-

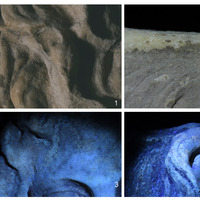

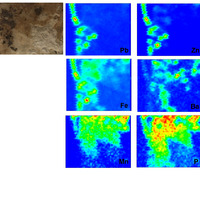

Macro‑imaging of the hair shows a yellow‑orange base layer overlaid by a brown stratum, with a third bright orange layer on certain curls. Identical treatment appears on the beard and drapery, while the skin shows exclusively a yellow layer. The eyes (contours, pupils, and eyebrows) and the junction lines between beard and skin are defined by painted brush strokes. The rear of the bust shows the same treatment of the hair. There is no preparatory layer on the pillar supporting the axial structure, although its contours are defined by a black line. Under UV light, the preparatory layer appears white and the upper layer appears black.

Microscopic examination confirms two paint layers on the hair, beard, and drapery—with bright orange highlights in the hair. The skin layer is thinner and translucent. In shadowed areas (temples, right side of the neck, décolleté), a translucent light brown layer overlays the yellow underlayer. The placement and gradient suggest intentional application to enhance volume and direct the gaze to the right—commonly seen in Roman painted portraits on walls or wood. The same effect appears in the drapery folds. Additionally, micro‑traces of gold leaf on the lower left of the drapery may indicate a former partial (or full) gilding. -

B 158. fig.2

B 158. fig.2

-

B 158.fig.1

B 158.fig.1

- Chemical analysis

-

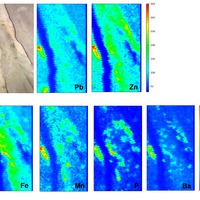

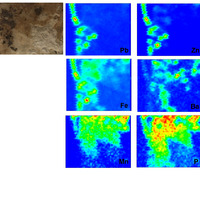

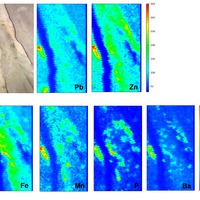

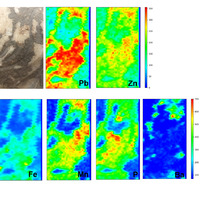

MA‑XRF spectrometric analysis was conducted on three zones—the hair, drapery, and support at the back.

The preparatory layer reveals an unusual and rarely attested composition. The combination of lead and zinc is generally considered a marker of a white pigment used in the 20th century, known as lithopone. This material consists of a mixture of zinc oxide, zinc sulfide, titanium dioxide, and lead white. However, the absence of sulfur and titanium on the bust, along with the condition and degradation of the pictorial layers, leads to the exclusion of this being a modern pigment.

The dark brown color indicates the presence of hematite and suggests the use of earth pigments. These earths were probably mixed with manganese oxide, a black pigment used since prehistoric times. The presence of phosphorus also indicates the possible use of carbon black. It seems that the dark pigment of the surface layer is composed of a mixture of earths with bone black and manganese black. Considering the thickness of the layer and the presence of a preparatory stratum, the visual effect would have been quite dark across the entire surface. -

See all items with this value

B 158. fig.4

B 158. fig.4

-

See all items with this value

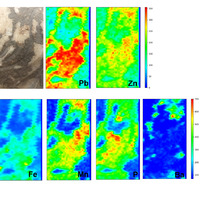

B 158. fig.5

B 158. fig.5

-

See all items with this value

B 158. fig.6

B 158. fig.6

- Under painting traces

- n.d.

- Pigments

-

Carbon black, yellow ochre.

- Binder

- n.d.

- Stratigraphy

-

Preparatory layer of lead white and zinc.

- Shading

- no

- Metallic traces

-

Gold leaf on the drapery.

- Tools marks

-

Black stroke on the support, 3 cm brushstroke.

- Background colour

-

Support identical to the subject.

- Apparent marble parts

- no

- Restorations

- no

- Polychromy technique

- The brush lines outlining the eyes and beard are applied over the yellow base and may represent preparatory sketches for further finishing—a technique well documented in sources and suggested for various statues. However, since they lie on the preparatory layer, they may also be the visible paint itself.

- Imitation of other supports

- metallo

- Predominant colour

-

Semantic bichromy brown-dark brown (face) - black

- Polychromy type

-

The polychrome finish was therefore applied to all parts of the bust, characterized by various shades of yellow, orange, and brown-black. The flesh was a light yellow with brown detailing applied by a fine brush; shadows were also enhanced in brown. The movement of the hair and curls was faithfully rendered with color: on a bright yellow-orange base was superimposed a dark brown paint with areas of orange highlights; shadows were likewise rendered in black or brown. The drapery was yellow, and the folds marked in brown likely featured a complete or partial gilded finish. The contrast between the dark color of the hair, the pale tones of the flesh, and the vivid drapery was intended to animate the statue. The same can be said for the lines emphasizing the facial features. The nuanced bichromy—carefully executed, possibly partially or entirely gilded—does not seem to follow the illusionistic realism style, despite a deliberate search for depth and volume achieved through the interplay of light and shadow. These effects raise the question of what meaning the artisans sought to convey through the colors. Both possibilities—dark tone or gilding—find meaningful parallels.

The dark tone attributed to the statue of Serapis refers to a broader tradition concerning the appearance of Egyptian gods, traces of which can be found, for example, in Plutarch.